Shrinking Labor Force is Top Challenge for Global Hospitality, Tourism & Service Industries | By Jeff Coy, ISHC

A shrinking labor force is the number one challenge facing the global hospitality industry, according to the International Society of Hospitality Consultants, which recently convened to brainstorm world issues and rank them according to importance.

Many of us, whether employer, employee or consumer, are beginning to feel the effects of a shrinking labor force in the service industries, but few of us understand the causes of a smaller workforce. Some major countries are in real trouble in the decades ahead. This report explores effects, causes and offers a solution for certain countries to better compete in the world marketplace.

Immigration, both legal and illegal, is a hot topic currently in the United States Congress, not because migration is a means of easing labor shortages, but because the USA wants to better control its borders --- to screen infiltration by terrorists. A new report by the Center for Immigration Studies found that 7.9 million people moved to the United States in the past five years, the highest five-year period of immigration since the peak of the last great wave of immigration in 1910. Of the nation’s 35.2 million immigrants, the new report estimates as many as 13 million of them entered the USA illegally.

For years, the US and state governments turned a blind eye on the millions of low-skilled undocumented workers that entered the US illegally from Mexico, East Asia, Europe, the Caribbean, Central America and South America. Now, what to do with those illegal immigrants is the subject of fierce debate on Capital Hill.

Traditionally, the US has been a country of moderately high immigration. About 12.1 percent of the current US population was born in another country. Some estimates put the immigrant worker population in entry-level positions at US hotels and restaurants as high as 80 percent.

In the 21st century, the world economy is a service-economy. Services require people. Therefore, any worker shortages have a greater impact on the service industries, such as hospitality, leisure, recreation, childcare, healthcare, assisted living, long term care and other personal services. The number of available jobs in the USA is projected to increase by 22 million by 2010. Yet the labor force is projected to increase by only 17 million, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The US hospitality and leisure industry is expected to grow by 2.1 million jobs between 2002 and 2012 (17.8 percent) which represents a faster increase than the 14.8 percent job growth for all industries.

Effects of a Shrinking Labor Force

Employees are going to be hopping from one job to another and from one industry to another as never before. They will not be as efficient and effective as their predecessors were. As consumers, we are going to feel like we’re not enjoying the same standard of living that we once had.

Neal Learner, reporter for the Christian Science Monitor, explains it this way: “You buy groceries at your friendly local food store and you have come to depend on the person behind the fish counter. You show up one day to buy your fish, and that person is no longer there because he’s changed jobs. The person who is there doesn’t seem to know what he or she is doing, and furthermore, doesn’t really care much about you. And you’re not the only one who feels this way. Other customers feel the same deterioration in service, and they choose not to go there anymore. Now that store is in trouble. Because it cannot find good people to serve its customers, its sales drop. You go back again and this time there is nobody behind the counter, and you have to call for somebody to help you.”

We can all feel the impact of a shrinking labor force at the corner grocery store, but the same feelings and impacts apply to hotels, tourist attractions and whole countries as they compete in the worldwide market.

Impact on Lodging

“In Nashville, a new general manager of major chain hotel sent a truck to a competitor’s property. On the side of the truck was a sign offering cash bonuses to employees willing to come to work for him. On the inside of the truck was a man handing out applications. At the Broadmoor Hotel in Colorado Springs, the average housekeeper accumulated almost 500 hours of overtime last year. When Disney Hotels was recruiting workers for its hotels and restaurants in Orlando, company representatives traveled to Pittsburgh, Rochester NY and San Juan, Puerto Rico offering $1500 relocation bonuses and a $100 airline ticket to anyone who would work for Disney for at least one year,” according to Valerie Ferguson, former chairman of AH&LA, the trade association of the nation’s $93 billion dollar lodging industry in her testimony to US House Committee on Education and the Workforce.

Impact on Tourist Attractions

Paramount’s Kings Island amusement park in Cincinnati, struggling to cope with a tri-state labor shortage, hired up to 300 European college students to staff its peak summer months. Another 200 workers were imported from other US cities. To accommodate its new recruits, the amusement park leased a University of Cincinnati dormitory and signed a $150,000 contract with Metro to provide expanded bus service to the park. Park officials say, “We’re going to have to be more creative in finding workers.” Importing foreign workers may seem novel in Cincinnati but it is a common practice in the amusement park industry. “I’m aware of a half-dozen or so facilities across the United States that have brought in foreign employees and put them up in a dorm room or hotel rooms,” said Joel Cliff, a spokesman for the International Association of Amusement Parks & Attractions. The biggest problem facing the amusement industry in the next decade is the shrinking labor force among high school and college-age students.

Cedar Point amusement park in Sandusky OH has on-site dormitories that can accommodate up to 3000 workers. Casino Pier and Water Park in Seaside Heights NJ has hired students from Ireland since the 1980s. And Paramount’s King’s Dominion, a sister park to Kings Island, housed 250 Europeans in dorms at Virginia Commonwealth University. Not only is this a problem in the United States, it’s a problem in England and France; they are hiring employees from other countries too.

Visionland, a themed waterpark attraction in Birmingham AL has broadened its recruiting range way beyond its normal 10 mile radius. ”We are now using international recruiting companies to find employees from other countries,” declared Kent Lemasters of AmusementAquatic Management Group (AMG), the firm that manages the park. “We are assisting these employees with housing and transportation. We are also recruiting more senior citizens because of their high work ethic and dependability. One senior is 79 years old. We have commissioned some of our top senior employees to recruit fellow seniors they know at church or social circles.”

Geyser Falls, an outdoor waterpark owned by the Choctaw Indians in rural Mississippi had to fill 300 jobs from a small town population of 6,000. “We didn’t have to import workers but we did recruit aggressively through other employees and at local job fairs,” according to Steve Mayer of Reno NV-based Cross Country Management, who spent the last four years as a consultant to the waterpark owners. “We spent a lot of time and money teaching our recruits necessary skills --- like learning how to swim before they could be life guards. Another problem is the school schedule as many high school and college-age employees leave their jobs early, before the season ends. We created a bonus (up to $1.00 per accumulated hours worked) for employees who stayed with us to the end of the season.”

Impact on World’s Most Visited Countries

France, Spain, USA, China and Italy are the world’s most visited countries by international travelers. The tourism product-service offered by these countries will be significantly affected by a shrinking labor force over the next several decades. Of the top five most visited countries, the quality of the tourism product-service in Spain and Italy will be the most severely impacted due to fewer people in the workforce.

In the USA, the tourism product-service is the country’s top export. Tourism and hospitality services consist of a heterogeneous collection of firms and employees that provide a memorable and pleasurable experience for both domestic and international visitors. When labor shortages impact the transportation, lodging, food service and attraction companies, there are fewer employees left to deliver the high-quality service or experience. Therefore, the quality of the service suffers. Poor service results in negative experiences and visitors decide not to return.

Here’s the bottom-line impact of a shrinking labor force:

- A decline in personal service. There’s nobody to help you.

- A rise in self-help. Do it yourself.

- Less convenience, more hassles, longer wait times.

- More self-service.

- Lower quality of life.

- Less productive per person as a country.

- Less competitive as a country in the world market.

- More international migration of workers.

- More companies will relocate offshore.

- A possible brain drain from some countries.

- Capital investment will flow to countries with abundant labor

Think of the adjustments we’ve already made: Online education courses eliminate the need for instructors, Microsoft Office eliminates the need for secretaries, ATM machines eliminate the need for bank tellers, self-check-out at Wal-Mart and Home Depot eliminates the need for store clerks. Self-check-in kiosks at hotels eliminate the need for front desk clerks. Credit card readers at parking lots and movie theaters eliminate the need for clerks and ticket-takers. Are these adjustments real advances? Perhaps. Is automation doing the boring jobs that nobody wants? Maybe. Are we preparing for a life of no service, except self service? Yes. Are we effectively training our smaller workforce for higher-skilled technical jobs? Not really.

While the effects of a shrinking labor force can be felt by almost everyone, the causes of a shrinking labor force are less well understood.

Causes of a Shrinking Labor Force

When you first delve into the Shrinking Labor Force issue, you quickly realize it is not the problem of just one occupation or one industry or even one country. It is not the problem of just the advanced nations, but rather it is a global problem that affects almost all of the major countries of the world. Why is this? What are the causes of a shrinking labor supply in so many countries?

- Fewer babies born

- People living longer

- Slowing population growth rate

- Aging of the population

- Fewer persons in the working-age group

- Fewer working-age persons participating in the labor force

- Geographical separation of jobs and workers

- Net immigration

Every country has a profile regarding these factors which places it in either mild or extreme jeopardy of losing much of its labor supply in the next few decades. The Workforce 2020 Report by the Hudson Institute concluded that the United States will face a tight labor market in the coming decades. However, the future labor supply in the United States is more favorable and exhibits greater growth potential than in almost any other advanced country and is much more favorable than most.

Fewer Babies Born

The birth rate in the USA in 2000 was 2.1 children per woman, which is considered the population replacement rate. Almost all industrialized nations fall below the population replacement rate of 2.1 live births per woman, which has led to an increase in the proportion of older people relative to the younger population.

The total fertility rate was over 4.5 children per woman in Pakistan, Guatemala, Malawi and Liberia in 2000. However, total fertility in many developing countries --- notably China, South Korea, Thailand, and at least a dozen Caribbean nations --- is now at or below replacement level. While over-population used to be a major concern, most countries are now concerned with slowing population growth.

Some countries face an actual decrease in population size, and they worry about the impact on their labor force, ability to produce and standard of living.

People Living Longer

Another big factor is the mortality rate decline. Spectacular increases in human life expectancy have resulted from earlier improvements in food production, distribution and nutrition for large numbers of people followed by later improvements in sanitation, medicine and social order.

Life expectancy at birth exceeds 78 years in 28 countries. Life expectancy at birth reached 80 years in Japan and Singapore in 2000 and reached 79 years in Australia, Canada, Italy, Iceland, Sweden and Switzerland. Levels for the USA and most other developed countries fall into the 76-78 year range. In Eastern Europe, people live an average of 66 to 75 years. The normal lifetime in many African counties spans fewer than 45 years.

On average, a person born in a more developed country can expect to live 13 years longer than his/her counterpart in a less developed country.

So, for most developed and developing countries of the world, declining birth rates (fewer babies born) and declining mortality rates (people living longer) have two effects:

Slowing of the Population Growth Rate (not a big deal) Aging of the Population (a very big deal) Slowing Population Growth For years, many countries were aware their population growth was slowing and aging, but there was no cause for alarm until demographers warned about the possibility of declining population size in industrialized countries.

In 2000, actual declines were reported in Spain, Italy, Russia and other countries. A United Nations Report suggested that populations in most of Europe and Japan will actually decrease in size over the next few decades.

Poorer countries have less means to support more children but they practice above-replacement fertility. Richer countries provide the economic rewards for having more children but they practice below-replacement fertility.

Governments have tried various methods to affect fertility with modest impacts in authoritarian states and even less impact in liberal democracies where government manipulation of fertility is a sensitive issue.

The tentative conclusion of demographers is that fertility in developed countries is not likely to go up significantly.

Aging of the Population

Population aging varies widely by region and country. But virtually all nations are now experiencing growth in their numbers of older people. Developed nations have relatively higher proportions of people aged 65 and over than developing nations --- ranging from 12 to 16 percent of the total population in most developed countries.

Demographically, Italy became the oldest of the world’s major nations in 2000. Over 18% of all Italians are aged 65 or over. Levels approaching or exceeding 17% are found in Greece, Sweden, Japan, Spain and Belgium. With the exception of Japan, the world’s 25 oldest countries are all in Europe.

The USA, with an older-aged population of less than 13% in 2000, is rather young by developed-country standards, and its proportion of older people will increase only slightly over the next decade. However, as the large number of baby boomers (born from 1946 through 1964) begin to reach age 65 after 2010, the percent of older Americans will rise markedly, likely reaching 20% by the Year 2030. Still, this figure will be lower than in most countries of Western Europe.

During the period 2000-2030, the projected increase in elderly population in 52 counties studied ranges from a low of 14% in Bulgaria to 102% in the USA to highs of over 250% in Malaysia, Columbia and Costa Rica and 372% in Singapore. The most rapid rate of growth in elderly populations is occurring in developing countries. Some elderly populations will more than triple by 2030.

An aging population is a very big deal because it changes the ratio of workers to non-workers --- i.e. the number of elderly that must be supported by the labor force.

The aging index is defined as the number of people 65 and over per 100 youths under 15. Among the 52 countries studied in 2000, five countries (Germany, Greece, Italy, Bulgaria and Japan) had more elderly than youth aged 0 to 14. By 2030, however, all 22 developed countries in the study will have an aging index of at least 100, and several European countries and Japan will be in excess of 200.

As the percentage of elderly increases in many countries, it will focus the spotlight on the dwindling percentage of working-age people in the population.

Fewer Persons in the Working Age Group

The potential labor force is defined as all working-age people in the population. As the population ages, there are fewer working-age people as a percent of the total population. In other words, there are fewer workers to support a larger number of children and older people.

The support ratio is another easily understood indicator to measure how many non-workers the labor force has to support. The support ratio is defined as the number of youth (aged 0 to 19) and the number of elderly (aged 65 and over) per 100 working-age people (aged 20 to 64).

In 2000, working-age people (20 to 64) were supporting an equal number or more youth and elderly in 9 countries: Guatemala, Philippines, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Zimbabwe, Morocco, Malawi, Liberia and Kenya. By comparison, the USA working-age group was supporting 70 non-working youth and elderly. France was supporting 71 with the UK supporting 69, Canada 63, Japan 61 and Germany 60. The Singapore working-age group supported the lowest number of non-workers at 46.

In 2015 the working-age group (20 to 64) in the USA will support 70 people in the non-working age groups (0 to 19 and 65 and over). In 2030, the support ratio in the USA will increase to 87. The USA worker support ratio may not seem alarming until you consider that not all working-age people are actually holding jobs or seeking jobs.

Decrease in the Labor Force Participation Rate

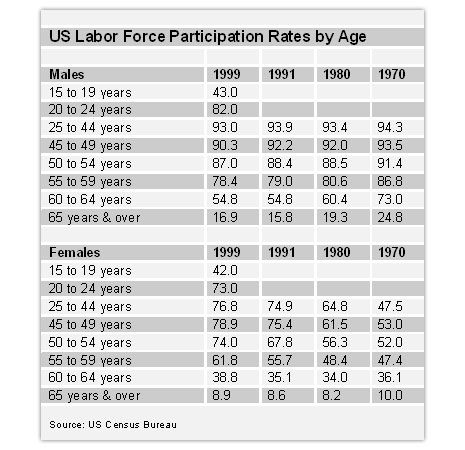

Let’s consider yet another ratio called the labor force participation rate. Of all working-age people, how many are actually holding jobs or seeking jobs. The labor force participation rate compares the actual number of people holding jobs or seeking jobs as a percentage of the total working-age population.

There are numerous reasons why working-age persons are not participating in the labor force --- gender, age, early retirement, unemployment, ill-health, care-giving responsibilities, lack of child care, undesirable work conditions, new technology and competing activities. Some are students or those involved in professional training while others simply do not wish to work.

Primary workers are typically men and heads of households in many countries, although many women now heading single-parent households are considered primary workers.

Married spouses, teens, college-age students are considered secondary workers. Younger populations are enrolled in the educational system, upgrading their skills prior to entering a higher skilled labor force. Older men retired early due to incentives and making room for baby boomers in the labor force, but now early retirement is a trend that may be reversing itself. The retirement age may rise as boomers reach retirement age. Working women tend to retire when their husbands retire. Unemployment rates are low due to the shrinking labor supply; however, some workers lose their jobs due to automation and new technology.

Labor shortages can have a variety of causes. They may occur because of a lack of geographical mobility on the part of the workers. They may be the result of a mismatch between worker skills and job skills. Other causes are changing demographics, rapid technological progress, business cycles, rigid wage structures and collective agreements. After a review of recent labor studies, the different causes of labor shortages can be summarized as follows:

- Rapid technological change. Leads to a shortage of workers with needed skills. Workers neither had the time nor opportunity to invest in these skills.

- Slow adjustments. It takes time for employers to recognize shortages and react to them, for example, by offering higher wages. Employers may be hesitant to raise wages or are tied to collective agreements or inflexible pay structures.

- Mismatch. Lack of adequate communication between employers and educators which leads to wrong educational decisions resulting in too few engineers, scientists and doctors, for example.

- Demographic trends. Low birth rate. Longer life expectancy. Low female labor participation rates. High number of people in retirement.

- Political disincentives. Increases in the marginal income tax rate push married working spouses into higher tax brackets. Poorly designed earned income tax credit so the family loses more than 49 cents of every additional dollar earned

- Insufficient regional worker mobility.

The role of migration in addressing these challenges, especially the issue of financing social security, was the subject of a recent United Nations Report. To deal effectively with an aging population and shrinking labor force, the report concluded that each country would have to implement a combination of strategies --- that migration alone seemed out of reach because of the extraordinarily large numbers of migrants that would be required. The UN Report attracted a lot of media attention and put the discussion of labor migration higher on the political agenda.

Predicting Future Labor Supply in 16 Developed Countries, 2000-2050

Does the absolute size of the labor force really matter, or do we need to be concerned only about its relative size to the number dependent people? No one knows. There’s no prior experience with falling labor supply over the long term.

For the past 30 years, most advance countries have been gradually or rapidly increasing the size of their labor force as the baby boomers entered the labor force and as women were integrated into the workforce.

During this period, growth was highest in the Asian “tiger” countries (Singapore, Thailand, South Korea), where the labor forces more than doubled. They were followed closely by the traditional countries of immigration (Canada, Australia, New Zealand and United States). The lowest growth was in the large European countries (France, Italy, Germany and Great Britain) and Japan, but even these countries expanded by their labor forces by 14% to 28% or several million additional workers in each case.

During this period of labor force expansion, the standard policy approach to tight labor markets has been to slow the rate of economic growth using monetary policy --- managing the right mix of economic growth, unemployment, inflation and interest rates.

However, if a future tight labor market results not from “too rapid” economic growth but from a stagnation or sustained fall in the labor supply, what policy approach should be used? This is a question posed by demographers Peter McDonald and Rebecca Kippen in an article, Labor Supply Prospects in 16 Developed Countries 2000-2050, they wrote for Population and Development Review.

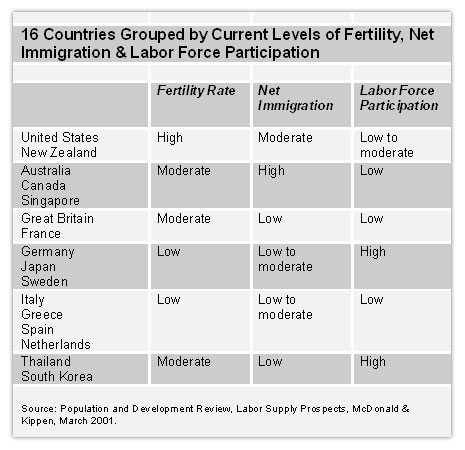

McDonald and Kippen grouped these 16 developed countries into categories according to their similarity in current levels of fertility, net immigration and labor force participation.

Next, they constructed different scenarios (combinations of fertility, immigration and labor force participation policies) and applied them to each group of countries to measure their impact on the size of future labor forces. As a result, they were able to recommend the best combination of policies that each country could implement in order to preserve or increase the size of its labor force in the future.

The United States can maintain a fairly brisk growth in its labor supply over the next 50 years without any change in its current levels of fertility, immigration and labor force participation. Even if the United States fertility rate were to fall from 2.1 to 1.8, the USA labor force would continue to grow, although at a considerably slower rate after 2015. If this relatively favorable future is cause for concern, other countries face a more serious situation.

New Zealand has both high in and high out migration rates. The out-migration is heavily concentrated among the 20 to 24 year olds. In addition, only 66% of working-age people actually participate in the labor force. An increase in the labor force participation rate could offset this trend of losing young people. The key issue for New Zealand is to have a sufficiently strong economy to enable it to retain its young people.

In Australia, Canada and Singapore, the key to avoiding a decline in labor supply is a continuation of immigration at least at present levels. To continue growth in their labor supply, these three countries will have to increase labor force participation rates. All three countries have declining fertility at present. Further falls in fertility will not affect labor supply for about 20 to 25 years, but thereafter, very low fertility (under 1.5) would have a considerable impact on labor supplies. Thus, if slow or negative growth in the long term labor supply is a matter of concern in these countries, current fertility needs to be maintained or even increased.

Germany, Japan and Sweden currently have low fertility and low to moderate immigration but high labor force participation. With zero net immigration and present levels of fertility and labor force participation, each of these countries faces immediate, sustained and substantial drops in the size of their labor force.

Over the next five decades, Japan’s labor force would drop from 67 million to 45 million, Germany’s would drop from 40 million to 21 million and Sweden’s would fall from 4.4 million to 3.2 million. Maintaining current levels of immigration would not prevent an immediate fall in Germany’s labor supply and in Sweden it would not prevent a fall after 2015. In Germany and Sweden, a rise in fertility from 1.4 to 1.8 would only cause their future labor supply to fall by a smaller amount (from 40 million to 34 million in Germany and from 4.5 million to 4.2 million in Sweden). For Germany, the best course of action, at least over the next 25 years, is to increase labor force participation for both women and older men.

For Japan, the most effective way to deal with the fall of its future labor supply is to implement a 3-part strategy: a rise in fertility to 1.8 over the next 15 years, higher labor force participation for women over the next 30 years and the immediate implementation of policies resulting in the net immigration of 200,000 persons per year. An increase in fertility and labor force participation of women would imply a major shift in the Japanese family system. For countries with a culturally homogeneous population, such as Japan’s, the in-migration on this scale presents a severe challenge.

Italy, Greece, Spain and the Netherlands have low fertility, low to moderate immigration and low labor force participation. A continuation of their fertility and immigration policies would produce, in each of these four countries, an immediate and substantial fall in labor supplies, and the fall would be sustained over the next 50 years. Adding to the number of immigrants improves the situation by only a small amount. The best way for these four countries to deal with falling labor supplies is to increase the labor force participation rate, especially among women, and this will require substantial cultural adjustment.

Thailand and South Korea have moderate fertility, low immigration and high labor force participation. Compared to the other 14 countries considered here, the fall in fertility in Thailand and South Korea is relatively recent. This means that currently they have a much younger age structure than the other countries and considerable potential for labor force growth over the next 25 years despite their fairly moderate fertility levels. Thailand’s labor force will grow from 35 million to 41 million in the next 15 years without any change in fertility, immigration or participation. South Korea is in a similar situation. Realistically, however, higher levels of participation of young people in education in Thailand in the future will somewhat reduce the labor supply projections.

Recommended Actions for Countries

Analysts see the United States, the primary engine driving world economic growth, facing a tight labor market in the next 30 years despite the fact that the future labor supply situation is more favorable in the United States than in most other countries considered in this study. While a slowdown in economic activity is often praised, the more likely outcome is that countries with falling labor supplies will not fare well, while the US economy will continue its growth. Capital, in turn, will follow such growth.

For countries of immigration (United States, New Zealand, Australia, Canada and Singapore), a drop in labor supply can be avoided through a continuation of their present fertility, immigration and labor force participation rates. Incentives for increased labor force participation of women and older men would lead to substantial growth in labor supply in all these countries. These incentives, for example, could reverse the early retirement trend in the 55-64 age group.

France, Great Britain, Germany and the Netherlands can prevent future declines in their labor supply if more working-age people joined the labor force combined with modest increases in immigration. However, to significantly grow their labor supply, these countries will have to allow immigration well above their current levels.

Sweden will have to double its net immigration each year to offset its decline in the labor supply in the next 25 years.

Italy, Spain and Greece could maintain their labor supply if they increased labor force participation rates for women and older men combined with modest increases in immigration. Both of these changes would require considerable cultural adjustments.

Japan faces the least favorable situation of all the advanced countries examined here. Nevertheless, the “optimistic” projection for Japan produces relative stability in its labor supply for the next 50 years. This optimistic projection requires a considerable increase in the labor force participation of women over the next 30 years, net immigration of 200,000 persons annually, and an increase in fertility from 1.4 to 1.8 births per woman over the next 15 years.

Implementing the best combination of polices to maintain or grow future labor supplies will prove difficult for some countries. For example, some “crowded” countries will resist fertility increases. Countries that lack a history of large scale immigration and have “homogeneous” populations will resist the immigration approach or face social and political instability. Countries with low labor force participation will have to make cultural adjustments regarding women and older workers.

All of these considerations concern the re-positioning of countries in the world market for the long term. This long term approach does not mesh well with the short-term monetary framework of economic policy in most countries.

The shrinking labor force is a universal problem for many countries that impacts service quality, economic prosperity and the ability to compete worldwide. The service industries --- including healthcare, travel, hospitality, food service, leisure and recreation --- are more affected. Service delivery systems are more people-intensive than traditional manufacturing systems. Almost all major countries face the threat --- from mild to extreme --- of a shrinking labor supply. For some countries, stopping the decline in labor force size will require minor changes. For other countries, it will require major changes over the next few decades.

Human Capital Crisis In Hospitality | By John R. Hendrie

Top Ten Global Issues and Challenges In the Hospitality Industry for 2006

Jeff Coy, ISHC

Mobile: 480-488-3382

Email: jeffcoy@jeffcoy.com

JLC Hospitality Consulting, Inc.

www.jeffcoy.com

P.O. Box 4090, 39401 N. 67th Place

USA - Cave Creek, AZ 85327-4090

Phone: (480) 488-3382

9 Hotel Waterpark Resorts Coming to Colorado | By Jeff Coy

Hotels Focus More on Family Fun Facilities | By Jeff Coy